Can Karl Popper help you learn to cook?

Philosophy of Science in everyday life series - Part I

Science is a niche activity in today's world; performed by experts and funded by governments. Like all specializations that constitute various nodes of the web of economy, there is not much need for people outside the field to familiarise themselves with its intricacies. But there is something fundamental in the pursuit of science that is worthwhile to be pondered upon by both non-scientists and scientists alike. It is what makes science, science. This combination of ideas that has more or less driven the course of human history since the Renaissance is today grouped under the umbrella term, Philosophy of Science. In the course of a few articles, I shall present some of our current ideas in philosophy of science from my perspective, and discuss how essential it is to the modern way of life. My aim is to break the train of thoughts in pieces of approximately 1000 words each, making for quick reads on the bus. A lot of the ideas presented below are from physicist David Deutsch's excellent book 'The beginning of infinity'. I read it in mid-2017 and have been ruminating on these concepts ever since.

To talk about the nature of science as a whole, we need to step out of science: into philosophy. Philosophy, unlike science, is not aimed at searching for the right answers. Instead, it focuses on what are the right questions to ask. And I am here to convince you that how the answers we have found till now can help you become a better thinker, in everyday tasks. Philosophy of science is the latest release in a series of human thought called epistemology. Epistemology investigates a very fundamental question we have struggled with for millions of years, How do we know what we know?

In the pre-modern era, epistemology was confined to priests and astrologers. All that has to be known was written in a holy book. The only knowledge that ever could be sought was the trivialities of everyday life, such as waging wars or building temples and churches. The progress of knowledge was along the lines of the saying

Necessity is the mother of invention.Basically, we made it up on the fly. For the largely religious subjects of the empires of antiquity, any significant question was answered by God through his/her/its messengers. A simplified version of their epistemology looks like this :

- Why is there something rather than nothing? Because God willed it.

- How should one live? As God and the priests dictate.

- How can we know the truth? By praying to God or by studying holy scriptures.

Well then, what do we know that they didn't know? What is the key difference between Newton's and Aristotle's thought processes? That brings us to right in the meat of the matter. Modern science starts by believing in the existence of the universe we live in. We believe that things are. That there is something rather than nothing. This part is the ontology of science. The belief in a consistent reality is essential to have any notion of what that reality is. So, for a moment, imagine there are no glitches in the matrix.

The existence of this reality entails the existence of absolute truths about this reality, which constitute knowledge. So far we have tackled the two questions

- What is? (Reality is.) and

- What is 'to know'? (To know is to know absolute truths about the reality.)

Today, we know that experimentation is a very important component in our pursuit of truth; it forms a part of our recipe for knowledge which we call the scientific method. As we shall see, the scientific method is an accurate summary of all that we know about how to know stuff. This method is like the user interface of philosophy; if you follow closely you could get things done without having to tinker with the wires inside the machine. The algorithm for acquiring knowledge, according to the scientific method is:

- Know the current ideas about the nature of stuff.

- Guess something about the stuff.

- If your guess doesn't fit in the existing logic system, invent ties to all previous observations. Now you have got a theory.

- Choose between good theories by designing experiments.

- Perform the experiment; it will invalidate some of the theories.

- Perform multiple iterations of steps 2-5.

|

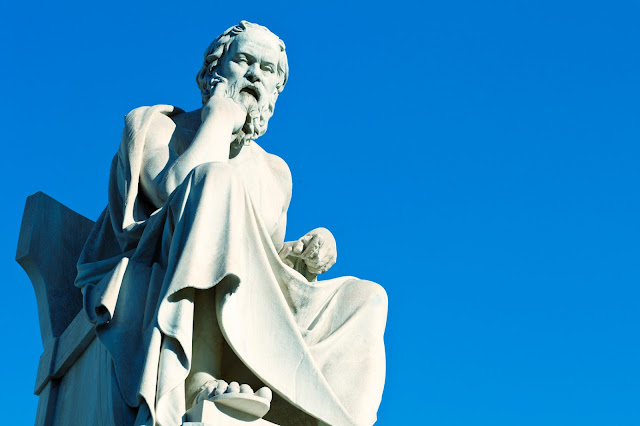

| Karl Popper, the progenitor of modern philosophy of science. |

Notice the vital role played by the notion of 'theory'. A theory is an innate idea, an educated guess about the nature of stuff, but a guess all the same. So why does this method work?

Twentieth-century philosopher Karl Popper seems to have given the ultimate explanation for the scientific method as we know it today. For all practical purposes, he defined 'science'. Karl Popper's epistemology is called falsificationism. It can be most appropriately summarised in the famous three-word quote from the show Game of Thrones

You know nothing.

And with that thought, I take your leave. In the next article of this series, I shall explain falsificationism and put it in context for your everyday existence. We will untangle the concepts of 'theory' and 'evidence'.

Stay tuned!

Comments

Post a Comment